I love street photography.

I am sick of street photography.

I need to qualify that remark, as much for me as for you.

Maybe it is too much avid self-saturation of the form, or trying too hard to find some relevance in it, but either way, I have started to “see through the makeup”. To see the artificial veneer of repetition for what it is.

First up, I am as guilty as anyone else of the thinks that are starting to annoy me and I recognise that I and everyone else, has the right to just ‘do” street photography however they wish (especially however they wish), but I am starting to want more, both from myself and from others.

Just like landscape, fashion, wedding and any other form of photographic endeavour, street shooting is heavily serviced with dozens (1000’s?) of talented shooters, who are all starting to blend together in content and intent. Everything, I suppose, settles for an accepted norm, some variations of that norm, then aberrations that create their own sub-genre or whither and die. The problem here is this blanket of normality provides a place where we can all hide as a like minded flock.

Street photography is an old form of photography. If you include candid photography of events and the realm of documentary journalism under it’s vast (vague) umbrella, it even goes back to the American Civil War with Brady and co. My first awareness of it, without even knowing what it was called, was the early 1980’s National Geographic style. It is basically a departure from documenting people in staged portrait images (as the technology forced), trying to get to the heart of an event and it’s consequences.

Cartier Bresson is often recognised as the father of modern street photography in the modern sense and his subject (usually Paris streets, but not always) helped to define the term “street” as a separate sub-genre of the more general documentary style, but I include Helen Levitt, Dorothea Lange, Eugene Smith, Sam Abell, Fred Herzog, Saul Leiter, Sebastiao Salgado, Pentti Sammaallahti and many, many others into the broader scope. I view them all as attempting the same thing, candid, real life, human endeavour and human condition story telling. The roots of street photography are in documentary photography, the roots of documentary photography are in a need for understanding.

Why am I so frustrated?

The common thread of modern street imaging seems to be based on a disconnected (and disconnecting) , semi abstract, emotionless style using dark humour, cleverness and coincidence as a badge of honour. Humour has it’s place, but should it be the pinnacle of an art form? We are turning street photography into a type of short form parody like political cartooning.

This reliance on a form of loose abstractness, held together by commonality in thinking is possibly leading to a trivialisation of the core of street photography and a reliance on gimmicks and cliche.

Where is the connection? Where is the emotion?

The very first lesson any NG or similar shooter will tell you is something like “know your subject, connect and understand, be patient”. By this I do not mean intellectual knowledge (research), but a deeper, more respectful understanding of the subjects themselves. Salgado’s work for instance, came from working in the finance industry, learning the plight of the people he worked amongst, then using the camera to convey what he felt and why he felt it.

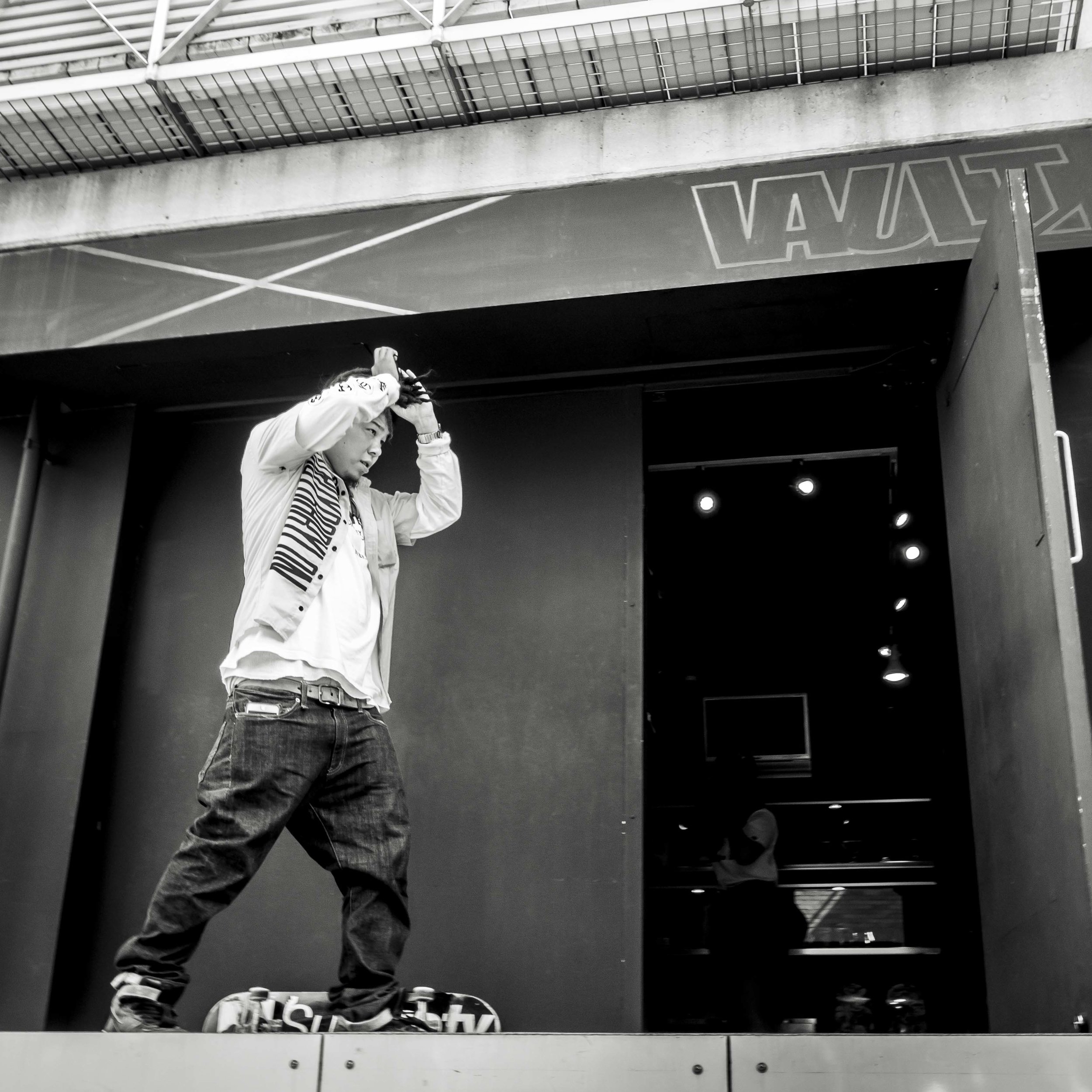

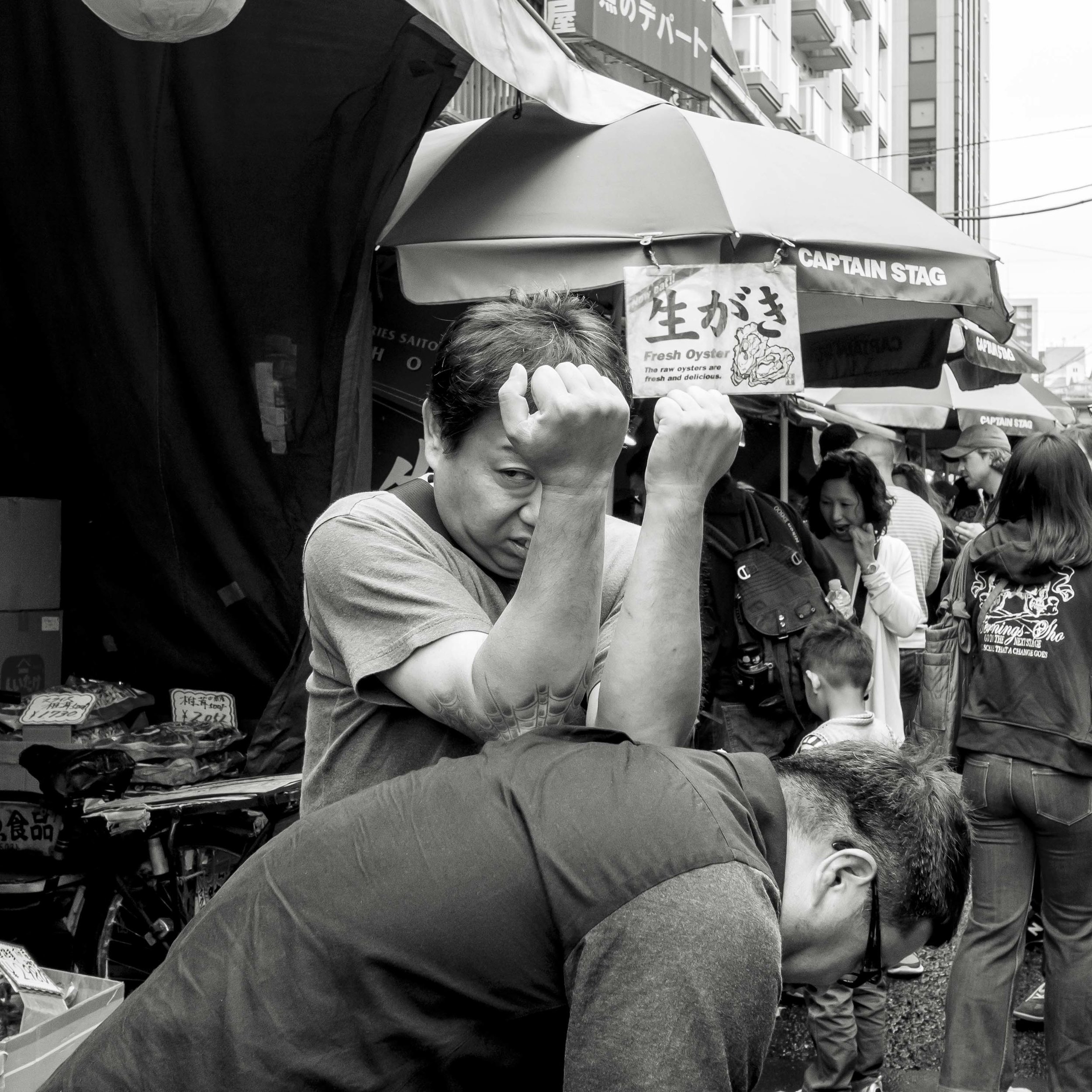

This is one of the few street images I have taken that I “respect”. The moment of desperate stillness and dignity captured against the shallow rush of humanity lets me see inside something bigger than myself. This is not what I usually manage to capture, so lets put it down to luck not effort.

What do you think? A deeper understanding of two brief moments in these peoples lives, or simply a photographically balanced coincidence. When you start to question, even your favourite images fall short.

There could also be a question of “Higher Art”, where the avalanche of similar images is simply over whelming my senses, numbing me to the basic goodness of these images.

A good image is a good image. If it triggers an emotional response, then, on some level , it is art by definition, but are we trying to funnel that response down the same pathways, cutting off others.

I like happiness in my street images. This is swimming against the tide and I know it, but I still like it.

Shock, awe, fear, confusion, aggression sell papers and to some extent art. What about genuine happiness, dignity, harmony or compassion? When you look at the work of early documentary and street photographers, their work is a balance of emotions. often this distinction is subtle. It may literally be a matter of inches or seconds between an negative or positive message. Even the hardened war photographer can find humour, strength and happiness in times of distress, (again Salgado looks for dignity and grace, not suffering, in his images of the poor and starving) so why do we look so hard for negatives to express our safe lives?

Why not?

Japan in particular has taught me that even in a strictly ordered society, where apparently personal unhappiness is high, people learn to grab every opportunity for happiness. They treat happiness as we treat dissatisfaction, as the anti reality, the denial of a fact and go against the flow. On any given Sunday, the Japanese express their hyper selves, letting it all out, before returning to the mundane.

I deeply hope that the stronger ethic of documentary and social commentary continues to exist alongside the shallower trends of street imaging. The erosion of journalistic integrity and the severe reduction in incentive for talented people to go the extra mile is being countered partially by an upsurge of self driven social media reportage, so maybe street photography, when the fad is over, will settle into a more harmonious relationship with the new “hard” documentary style.

I guess what I am worried about on a fundamental level is that street photography will go into the realm of “only interesting to those that do it” like so many other forms of specialised art. If we stop trying to connect to others who are not like us (non photographers), then only we will care, like some funny little club based on an obscure hobby.

I think street photography is worthy of more than that.