This is for me, but you can join in.

Process is a funny thing.

After shooting stills after thirty odd years, I don’t think much about the process, it just happens. Even if I take a decent break, there is little to no awareness of getting back in the swing, but I know I get more efficient the more I do. Process happens, it just does.

Select lens, aperture, check shutter speed and ISO, compose and shoot, re-compose-shoot and so on. Instinct and practice, not thought.

Video is new.

The processes, although coming surprisingly comfortably, are still new. This means I tend to dwell on process, spend too much time thinking about a to-do list of work methods or “shapes” to try and techniques to attempt.

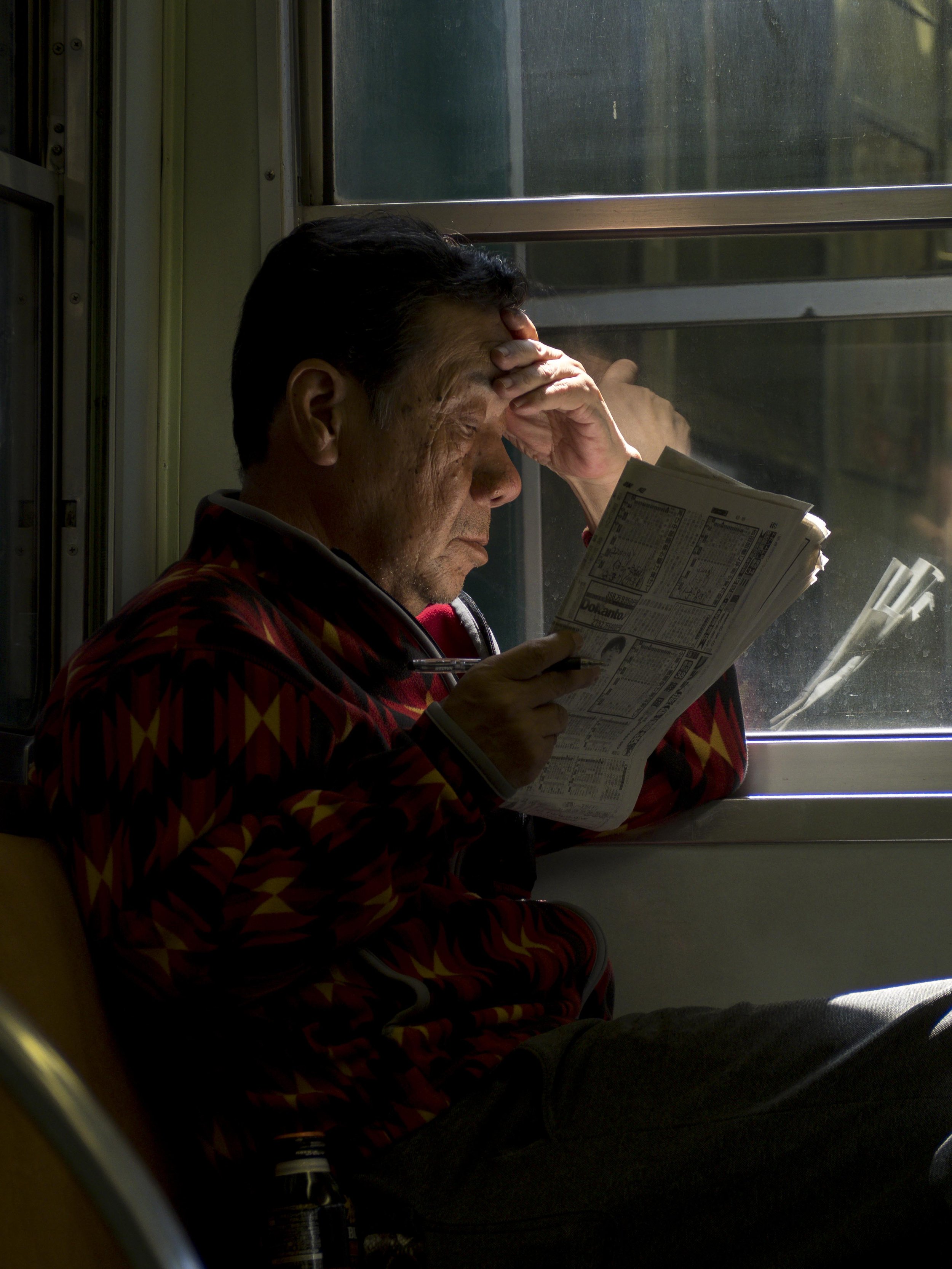

“Fashion Victims”, Tokyo 2017

I need to be able to “see” things organically and be able to react. At the moment there is much planning, which is fine, but the planning is over-riding my reflexes.

There is probably not a more certain way of curtailing creativity than concentrating on process. Creativity should bloom in a garden empowered by process, but the garden needs to move out of the way to allow the blooms to take shape.

If you push through and repeat over and over, eventually you get muscle memory freeing up your productivity, but that takes a while and productivity is not necessarily creativity.

I, in an effort to grow my video “chops”, will do this;

Concentrate on the subject.

Subject is all, the rest comes.

It is what it is, you just need to see it.

I concentrate on subject first with my stills, melding my personal view with my perceptions of the thing itself. I come to it with the practiced confidence of someone who has dedicated a lifetime to wanting to then practicing over and over.

Let a little obsession in, it helps.

Ironically the first step is get your processes in order. Make them invisible, effortless.

If you keep it simple, make sure you are organised and basically get your Sh#t together, then you can concentrate on the subject.

All you have to do is make sure you have all you need to get the job done, but no so much you are paralysed by choice.

Yeah simple ;).

My advice to myself is to keep the camera and lens combinations simple and fixed.

Work with what I have with light and angles, only meddling with extra stuff when I have to and “take it as is” is exhausted. Basically let the story tell itself, let the subject control the space and work as sympathetically with it as I can. Don’t push myself on it, let it show me what it has when it wants to.

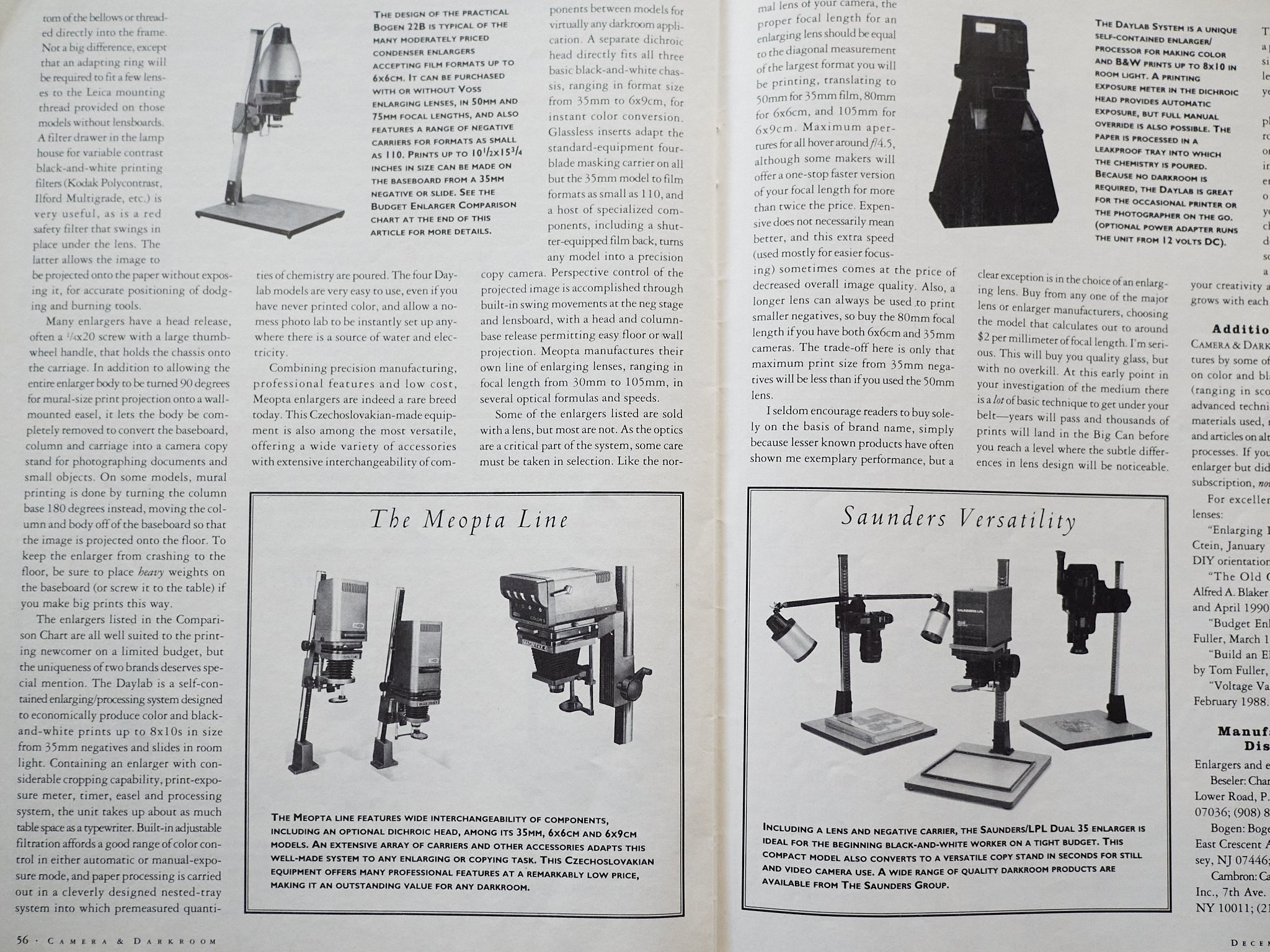

“Space Invaders”, Kyoto 2019

Over eight trips to Japan, one lens, the little 17mm f1.8 Olympus has done the Lions share of the work. Plenty of lenses have been lugged over there, cameras to, but at the end of the day, I can show a strong body of work taken with the 17mm and any one of a several cameras.

Breaking it down to more practical language, make a shopping list of what makes up the subject. Who or what are they, what are they about. Challenge yourself to summorise the story in front of you as succinctly as you can.

The other advantage of this is you tend to shun short term fashions and gimmicks, becasue these are process based.

My hope is, I will naturally develope compostions and movements just like I do with stills. Organically and fluidly, I just need to stop thinking about it.