“Cinematic” is one of those terms that is close to turning from an ideal, a goal of many, to a dirty word.

Misconceptions are partly to blame. No point in chasing a rainbow when you are not sure what one looks like or what you are hoping to find at the end.

To many, “cinematic” means shallow depth of field, lens compression, softness with a misty glow, flare, moody light ironically often with a flat grade and maybe a little unnecessary movement.

To top cinematographers, the ideal they are chasing is often sharp, contrasty, realistic, wide and clean.

Seriously, look at the big flicks of the last few years.

Barbie, Oppenheimer, 1917, The Creator etc. They hero staging and blocking, light, clarity, performance, beauty of shot and reality. Compare this to “cinematic” footage from a lot of Indie shooters and you will see a contrast of styles.

Lens choice is often the first divergence. Most emerging shooters lean towards longer and faster glass, cinematic masters will, but not as often and often not the same way.

My examples are grabs from one of the few jobs I have done recently but should suffice I hope.

A full frame 50mm at f2 is the common starting place for a DSLR style shooter chasing that perfect Bokeh and soft blurring as well as a way of hiding messy backgrounds or limited lighting.

You can work tight using details and hint at more, something the cash strapped Indie shooter may require.

A tight shot showing all the hallmarks of modern photography and videography (except it is not soft or “glowy” enough”). A longish lens (85mm) a wide aperture (f2.8) and single subject focus.

These are easy, almost a cheat to pull off especially in stills, but problems are many.

Shallow depth requires precise focus pulling (possibly promoting too much AF use), the subject is cleanly cut out, but the other people are sidelined because of it and the scene is also pushed to the back of the line.

Your eye is drawn to the few elements in the image, allowed to accept the superior optical effect of “cut out” sharpness and clarity.

They also resist movement from the shooter as too many hard to control elements are introduced such as focus, camera movement and long distances covered.

You can take plenty of these and they are easy enough, but they are all basically the same.

A semi wide 28mm on Super 35 (about a full frame 35-40mm) at f4 to f8 is more commonly used by the masters. For them, the whole scene is the key. More means more and although it comes with its difficulties requiring more attention to detail, more lighting, more props, it also comes with the promise of greater rewards.

Simply by getting closer with a wider lens (30mm), the subject becomes more dynamic, more animated and the viewer connects with their perceived closeness. The environment becomes an equal player, not a blurred-out backdrop.

Using wider lenses makes the cinematographer a presence in the scene. There is a creative dance between the subject and recorder. Intimacy becomes easy and real.

This shot was taken with a 30mm (15mm on M43) at f4 (f2 in M43) and has more cinematic elements. There is more scene, more interplay, the perspective looks more natural and the “blocking” is inclusive. It is tougher to get a decent still because of the many elements, let alone a superior moving shot, but tougher is often better when you pull it off.

This view allows for the story to evolve, the relationship of the players to shift, for blocking to take effect. There is opportunity to shift with subtle ideas and moods.

Sound is also more natural coming from the subject in a way the viewer feels is realistic. The two give-aways that things are not real are lens tricks (strong compression or unnatural expansion) and distant sound seemingly up close, are both avoided helping retain viewer immersion.

The same interaction with a long lens is static, boring, detached, a detail shot only and any attempt to move is telegraphed tenfold. Sound from the subjects if used is known to be trick of the tech, not a natural occurance.

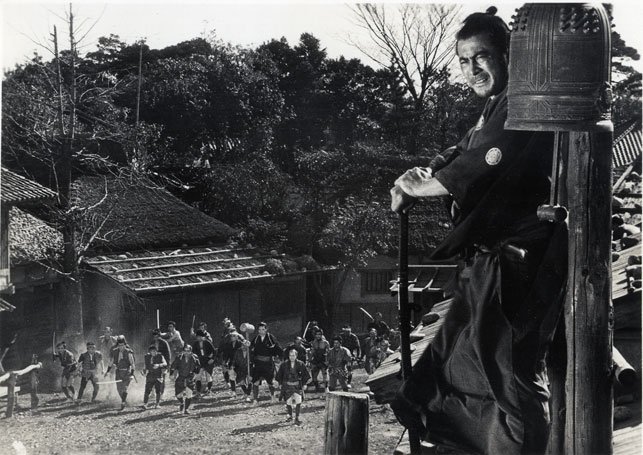

When a master cinematographer does use a long lens, say like Kurosawa, a big fan of them, he often used deep depth of field, hovering between sharp and soft as his background was always an element of the whole.

Balance and consistency are the key here.

Like a lot of things born of expediency though, these habits of necessity can become habits of emulation. A push for a certain in fashion look is often at odds with the end result, maybe even the end desire of the maker.

Want to be the next Wes Anderson, then shoot like him*, not like your favourite Vlogger wandering through the woods with his friends, hand holding things and making focus errors look like you meant them.

Be deliberate, be precise and above all be yourself.

*I don’t mean copy him, but take a leaf out of his book and create something that says you made it, not you made something like “X”.